The challenge of ubiquitous backwardness

Mr. Sukhadia, when he became the Chief Minister on 13th November, 1954, the geographical merger of the State was done. His predecessor chief ministers had enacted the Law on property abolition and the people of different regions of the State, particularly on the north-west border, were freed from the terror of dacoits. But the severe problem of universal backwardness plagued all the people of the state. In the vast thar desert spread over nearly sixty per cent of the area of three lakh forty thousand square kilometres of Rajasthan, the people of the country were able to produce a little bit of kharif crops.

About 28 per cent of the area was under agriculture. Out of this, irrigated land was only 12 per cent out of which only 3 per cent of agricultural land had access to irrigation through canals. In the entire state, only 13 megawatts of electricity was available at that time, which could have seen light in the capitals of the princely states and some major towns. The rest of Rajasthan lived in darkness.

Like the miserable state of electricity, drinking water, irrigation, agriculture and roads, the situation of education, medicine, industry, etc was worse. The literacy rate was only eight per cent and the female literacy rate was only two per cent. At that time, there were about 5000 schools and 24 colleges in the state. For example, today's district headquarter Hanumangarh town had only one primary school and one middle school at Hanumangarh Junction. There was one high school in sangria and Sriganganagar. In Sriganganagar, there was an intermediate school with high schools where education was upto the twelth. After passing the intermediate test, the students of Sriganganagar had to go to Bikaner for education because there was no degree college in Sriganganagar. This legacy of backwardness was received by Shri Sukhadia. It was a big challenge to transform it into holistic development and prosperity. It required a lot of financial resources. The state's own resources were meagre. On the other day, our first prime Minister, Shri Jawaharlal Nehru, started an innovative ritual of development through five-year plans by constituting the planning Commission. The process of providing financial resources to the States for implementation of development schemes was initiated by the Planning Commission. About two years after the formation of Rajasthan, the first five year plan was built in the country. 54 crore 15 lakh for the first five Year Plan (1951-56), Rs 102 crore 74 lakh for the second Five Year Plan (1956-61), Rs 1961-1966 crore 212 lakh for the third Five Year Plan (70), 1966-69 crore 136 lakh for the annual plans of 76 and IV 308 crore was sanctioned for the five Year Plan (1969-74).

Today, when we talk about the eighth five Year Plan of the Rs. 12, 000 crore rupee and the Rs. 28, 000 crore rupee plan, the financial provision of Mr. Sukhaadia's chief minister's time plans is not only a meagre but rather unbelievable.

The first budget of the state of Rajasthan was made in 1950-51 with revenue receipts 1460.53 lakh, revenue expenditure 1391.82 lakh and capital expenditure of Rs. 200.53 lakh. About 10 years after Mr. Sukhadia's chief minister, this budget increased considerably. In the budget 1965-66, a provision of Rs. 7968 lakh was made on account of revenue receipts and 8614 lakh in revenue expenditure. Continuous efforts were made to augment the internal financial resources of the State with a view to maximize expenditure on development works and social services under the five year plans. The state budget for the year 2000-2001 provides revenue receipts of Rs. 11222.57 crore and revenue expenditure of Rs. 14569.27 crore. Further, a provision of Rs. 7105.41 crore on capital receipts and Rs. 3871.5 crore on capital expenditure has been made.

The gift of water to the dry earth

Mr. Sukhadia went to the village village and dhani in the desert terrain and saw the people migrating there to battle the menace of famine and to save their cattle. Every time he returns from there with a heart full of compassion for human tragedy. He was determined that whatever is to be said, the dry land will have to be inundated with the gift of life-giver water for centuries to come.

In those days, there was a dispute between India and Pakistan over sharing of river water. The World Bank, on the initiative of the then prime Minister, Shri Jawaharlal Nehru, accepted the resolution of this dispute. On the suggestion of Shri Sukhadia, Nehruji persuaded the World Bank president to see this desert terrain of Rajasthan. Looking at the endless deserts and the difficult situation of the inhabitants here, the World Bank president, Mr. Blake, announced that this is the territory of Rajasthan, the first authority on this water. If this water is not used to wipe out the thirst of this endless desert, it will go waste into the Arabian Sea. If that were so, there could be no greater irony in the human tragedy. On this humanitarian basis, the "Indus-Water treaty" of water sharing and use was prepared, which was signed by India and Pakistan on September 19, 1960 in Karachi. According to this, India got the right to use the entire water of the Ravi, Beas and Sutlej rivers.

Dreams Come True

Rajasthan’s leadership has seen the dream which paved the way for the realization of the Treaty. First in the early twentieth century, the former Maharaja of Bikaner. Shri Ganga signh had conceived that some of the terrain of Bikaner state can be made available to water via rivers of Punjab. He has not only conceived but also empowered the use of water from the Sutlej River on the basis of indomitable courage and prodigious diplomatic skills, and in the shortest time he built the gang canal, the desert area of the northern western part of Sriganganagar district, to be green and prosperous. On October 27, 1927 Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya had started the launch of a ritual in the gang canal by worshipping the Vedic system. At the same time, Maharaj Gangasingh had dreamt that bottomless waters of the rivers of Punjab can be supplied to the rest of the state of Bikaner and the thirsty land of many other states of the neighbouring States . After 15 years of his passing away from the inspiration of Maharaja Gangasingh, Mr. Kanwarsen, a young engineer serving in the state of 1948, had also rightly dreamed that a canal was extracted from the water of river Beas from the rivers of Harikand at the bottom of the Sangam and Beas streams. , it can give a gift of greenery and prosperity to the entire territory of north-west Rajasthan. This terrain is where the mythological Saraswati river was flowing. In this terrain, the relics that are found in Kalbanga prove that the area was inhabited by a great civilisation about five thousand years ago. The recent geological surveys have also proved that the Saraswati river is not merely a fantasy of mythological gazian, but it was about five thousand years ago that the river flowed from Punjab to the mouth of Kutch. It is not just a coincidence that the Rajasthan Canal was built on the path of the river of the ancient Saraswati.

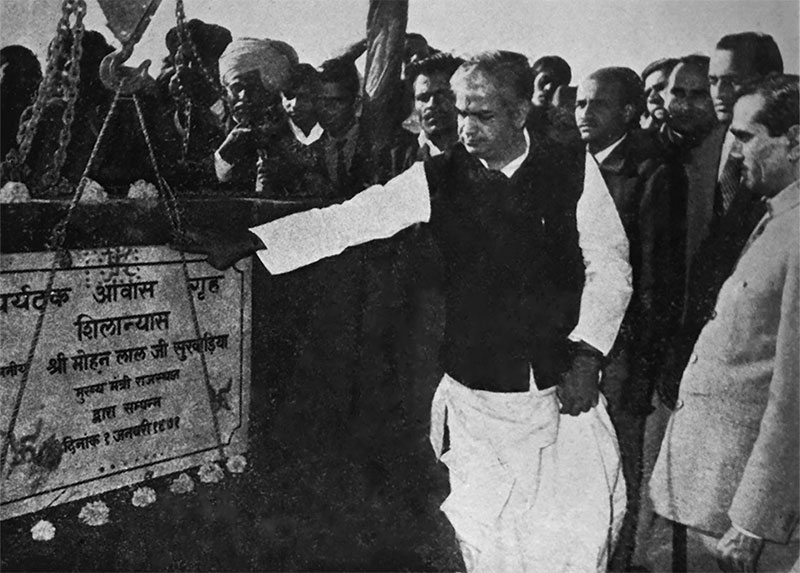

The third one to be dream of it was Shri Mohanlal Sukhaadia, former chief minister of Rajasthan. Even in his view, the permanent solution to the elimination of famine and scarcity in Rajasthan could have been possible through the Rajasthan Canal. He became the chief minister in November, 1954, and only two months later, in January, 1955 he secured an agreement with the concerned States to make 8 million acres (M. A. f) water out of the water from the Sindh River Group for Rajasthan. The agreement proved to be of great importance in securing the interests of Rajasthan in the coming time.

Rajasthan Canal Sriganesh

With the financial resources of the State being very meager, the state government duly cleared the Rajasthan Canal project vide all formalities tax Order dated 27th July, 1957 on which an expenditure of Rs. 66.67 crore was estimated. It also included the amount of contribution of Rajasthan in the cost of headcurves. In these estimates, 13.58 lakh hectares of land was proposed to be provided irrigation facility by Rajasthan Canal. Out of this, 3.64 lakh hectare was provided with irrigation across twelve months. On permanent solution of water sharing by Indo-Pak Treaty, the canal project size was expanded in the year 1963 and the estimated expenditure on the project was increased to Rs. 184.09 crore.

It may be mentioned here that in the second Five Year Plan (1956-61) of Rajasthan, a total provision of Rs.102.74 crore. The third Five Year Plan (1961-66) was also only Rs. 212.70 crores. In view of this shortage of amount, only one irrigation scheme of about 200 crore rupees was really a matter of exceptional courage and confidence. In such a financial situation, sanctioning the project by the Planning Commission and the irrigation Ministry of the central government was not less than a miraculous achievement.

The task of realizing this gigantic project was also less miraculous. In spite of the meagre financial resources, Mr. Sukhadia made a systematic effort to build the Rajasthan Canal project as the Golden Fate line of the happy future of Rajasthan desert state. Though the progress of implementation of the project has been relatively slow, the pace could not have been even faster, keeping in view the available resources. Shri Sukhadia had made efforts to take the project to the Government of India by considering it as the national level project, but the central government did not feel it appropriate to do so. The required amount of foreign assistance could not be available. The construction work of the canal project started between the geographical location of nature. The part of the canal, which was dug after the labour of the weeks, was filled with a two-day intense sandy darkness. There was no natural source of drinking water anywhere in the vicinity. There was no road connectivity. Four wheelers on this terrain were difficult to move. In spite of all this situation, the first phase of the main canal, 80 miles, was completed by Shri Sukhadia on July 8, 1971 when he resigned from the post of Chief minister. The remaining work up to 122 miles after 80 miles was in progress. The work of Norangdeer, Rawatsar, Joravapura, Khodan, Khetaoli, Thantar and Kannur distributor canals and Suratgarh branch was almost completed. Further, the work on the distributor canals, Sardarpura, Chuli, Jasabhati, Somesar and Bhoja was being completed on priority basis. About one crore rupees worth plantation was done to prevent the sand from falling into these canals at the time of thunderstorm and on the banks of nearby dunes and canal.

As a result of all these intensive efforts, in the last year of Shri Sukadia's rule, about one lakh 80 thousand hectares of agricultural land was provided with water for irrigation from this canal project. In the previous year 1969-70, there was irrigation in one lakh thirty eight thousand hectare of agricultural land.

Other Irrigation Projects

The work on Kota Barrage and its left and right canals under Chambal River Valley plan was completed. About one lakh 52 thousand hectare of agricultural land was provided with water for irrigation in the year 1970-71.

There was considerable progress in the work of the Beas multi-purpose project. The main task of 8 medium irrigation projects was completed in the last year of Shri Sukhadia's rule. Work on the grapes, Gopura, Bhimsagar and Meja feeder schemes was also undertaken. In addition, out of 84 minor irrigation projects, 35 works was completed. The production of foodgrains was about 76 lakh tonnes in the year 1970-71 as a result of availability of irrigation and use of fertilizers, pesticides and other improved methods. At the time Mr. Sukhadia became chief minister, the total foodgrain production was only about 3.1 lakh tonnes. That was the major step towards the prosperity and self-sufficiency of the people of the state. Mr. Sukhadia saw this dream come true.

In addition, schemes worth one and a half crore rupees were sanctioned for each district under which the small farm was provided with loans and grants for irrigation, livestock, seeds, etc. These programmes also paved the way for agriculture-related occupations such as animal husbandry, dairying, orchards, etc.

Considering cooperatives as the mainstay for all round development of agriculture, 92% of villages and 41% of farmer households were linked to cooperative movement. First in the state, a spinning mill was established at Gulabpura in the cooperative sector. In Rajasthan, particularly in its desert area, the activities of Rajasthan ground water were extended in view of the special importance of groundwater. 3513 wells were made more deep, which started providing irrigation facility to about 3,000 hectares of additional agricultural land. The survey conducted by the ground water board revealed that there is huge stock of ground water in the lathi-Chakan areas of Marwar-Chaura and Jaisalmer district. Till 1971, 22 towns were provided with safe drinking water. In addition, 299 rural water supply schemes have been completed. The scheme of safe drinking water without fluoride in Bankpatti was started by Shri Sukhadia.

Revolutionary land Reform

The second dream was to provide full ownership of agricultural land to the farmers by making them free from the exploitation of landlords . The movement of the Pramandmandal in Rajasthan was basically against the despotism and exploitation of landlords. The Kisan agitation of Bijauli was a burning example of this. The feudal system had terrorised the rural masses of the entire Rajasthan. The landlords used to take a variety of painstaking and murderous ways. The poor and helpless farmers cultivate farmland, water crops, protect them and fill the threshers with grains. Shri Sukhadia had agitated as a combative activist of the division to end the same exploitation. First, naturally, his first step in the state cabinet member's practice and then the Chief Minister was to give full ownership of land to the tillers by eradicating the ' fief ' system. As soon as the law was passed by the Legislative Assembly, the poor farmer, who had acquired the land, from the same day, became the owner of the land. The revolutionary laws pave the way for liberation and prosperity of farmers by way of land ownership and exploitation of 4780 villages.

The Greatest Revolution of the Century

Under the Rajasthan Tenancy Act, 1955, which was implemented for the new regime of land reforms, the state had three categories of food-holder tenants, self-appointed khatedar and non-food holder tenant farmers. Similarly, rules for appointments of revenue courts, revenue officers, preparation of rights, duties, maps and land articles, maintenance, revenue and rent arrangements, bifurcation of land assets etc. In the year 1960, Shri Sukhadia has amended the Rajasthan Tenancy Act to determine the ceiling of holding. The upkeep of these public welfare laws was ensured to a great extent by keeping an eye on implementation. This was the greatest silent revolution of this century for a state of Samantavadi background like Rajasthan. The inspirer, originator and regulator of the revolution was Mr. Sukhadia in the right sense. It may be mentioned that in some of the so-called progressive states of the country, the law on land reforms was made a long time after Rajasthan's initiative. In the words of former union minister, Shri Navalkishore Sharma, it was natural to have a deep tradition of zamindari and feudal practice in the land of traditions. Sukhadia took the land of reforms on these roots. Snatched right from the hands of the owners to empower the land-farming families and to provide land to the landless, Sukhadia was the successful chief minister. The passage and implementation of land reforms laws in the Assembly was indeed a difficult task. The first and second assemblies of Rajasthan had the majority of the ruling Congress party, but the opposition was also very vocal. Some of these members were associated with the ex-houses and the landlords. When the land reforms were implemented, a massive agitation was started on the part of the landowners. They were outraged that the kings of the first rulers were now being taken away by the land of the landlords and the land owners. On the streets of Jaipur, there were big procession of landowners in which many people had swords in their hands. Mr. Sukhadia strongly faced this agitation. The agitation failed because of the government's strong will and not under compulsion for land reforms. With this, one of the reasons was that in order to maintain the livelihood of the landlords, he was provided with his own land and compensation under the Pant award. The implementation of the land reforms programme was ensured on account of the rigid policy of the government.

Mr. Sukhadia was deeply impressed by Sant Vinoba Bhave. They looked at the Bhoodan movement that they had run as a non-violent revolution in the field of land reforms. On the invitation of Shri Sukhadia, Sant Vinoba Bhave visited Rajasthan extensively. With the support and cooperation of the State Government, the land donation movement was not found in any other state in Rajasthan. Lakhs of acres of land were received in donations and allotted to the landless. In this regard, the land donation committees of the landowners were recognised as gram panchayats by making separate laws.

Establishment of Panchayati Raj

Shri Sukhadia considered the establishment of Panchayati Raj on the basis of land reforms as well as democratic decentralization as necessary for the holistic development of rural areas of the State and the effective participation of the masses in power. On the occasion of Gandhi Jayanti on 2nd October, 1959, the then prime Minister, Shri Jawaharlal Nehru, in a massive public meeting held at Nagaur, ignited the Panchayati Raj system. Rajasthan was the first state in the country to take initiative in this direction. Under this objective more and more administrative powers were given to Panchayati Raj institutions. They were also given judicial powers by setting up Nyaya panchayats. Addressing him at the conferences of the administrative officers, Shri Sukhadia expected him to create a rural perspective. The officials will have to work hard and make similar approach to make the development works of the countryside as per the Rajasthan tradition a success. There was strict guidance from Shri Sukhadia that no development right should be transferred without consulting the head of the Panchayat committee.

During the tenure of Shri Sukhaadia, Panchayati Raj institutions had three elections in 1959, 1962 and 1965. The tremendous enthusiasm of the rural masses towards these elections has been manifested by the fact that the percentage of voting in these elections was higher than the percentage of votes in the Assembly and Lok Sabha elections. At some places, the turnout was 95 per cent.

In view of the enthusiasm of the general public towards the Panchayati Raj System, a study group was constituted under the chairmanship of Shri Sadiq Ali, then MP, to assess the implementation and suggest measures to make it more powerful. Based on the recommendations of the Study group, Gram Sabhas were recognized as institutions of law and were made the basic basis of Panchayati Raj. It was made mandatory for sarpanchs to hold Gram sabha meetings twice a year in every village. In these meetings of Gram Sabhas, it was necessary to furnish panchayat budget, audit report, annual plan, development details. Also, it was necessary to inform the Gram Sabha about the progress of the rural Cooperative Society and Primary School. The same was also required to be reported in the Gram Sabha by the Gram Panchayat for allotment of land, mutation, conversion, etc. The right to information was made available to the rural masses through these meetings of the Gram Sabha. This could not only keep a watch on the activities of the Gram Panchayat but also ensure their active participation in development programmes by their suggestions.

The total foodgrain production in Rajasthan in the year 1954-55 was 3.1 lakh 18 thousand tonnes, which was inadequate in view of the state's population needs. In order to make the gram panchayats participative by the State Government in its efforts to increase the expansion and production of agriculture sector, 15 Bigha lands were allotted to each panchayat to motivate the common farmer to adopt the new farming practices. S. 45 Bigha land was allotted to each gram panchayat of desert area. In those days, the Panchayati Raj institutions were almost fully responsible for the distribution of improved seeds and fertilizers. The principal, development officer, agricultural officer and Sarpanch were engaged in the same task at the time of sowing. They motivate the farmers to dig the mines to make compost and adopt advanced methods of cultivation. The training programme was given great importance to the physical and practical knowledge. The development officers were sent to live in a nearby village for about ten days. There they cut the harvested crop with the members of a peasant family all day, dug the prescribed length along the field at the place of the farm, the compost of the chaat and the depths, and they would fill the green leaves, dung, etc., and explain the benefits to the farmers.

It may be mentioned that in those days, chemical manure and improved seeds were distributed free of cost. But, in spite of that, traditional farming farmers looked at them suspiciously and were reluctant to use them even as a test. Therefore, a concrete effort was made by the Gram sevaks of Panchayat committees to motivate the farmers in village villages to use them. He was also told how to prepare the field before sowing, sowing the seeds at a certain distance in a straight row, how long should the irrigation be done and how to free the fields from weeds and harmful insects? Initially, the farmers were not convinced that even those who wear pants could have any knowledge about farming. It was indeed a difficult task to persuade them to earn their trust and to agree to use the new methods.

After tireless efforts, the farmer who had agreed to it, used chemical manure and improved seed as a test on his field. A notice board on the ridge of the field and the quantity, area and date of the chemical manure and seed used on it. The villagers were shown the increase in production by using the new method.

The major credit for Rajasthan's Green revolution and self-sufficiency in foodgrain production goes to the above efforts made to popularize new methods of cultivation in the initial years of Panchayati Raj with expansion of irrigation facilities.

Importance to Zilla Parishad

Initially, the work of the Zilla Parishad was confined to coordination and inspection. But it did not ensure their active participation in development works. The state Government, by taking a bold decision expressing its full faith in democratic decentralization, would transfer the primary health centre, Maternity and Child Welfare Centre, Ayurvedic dispensary and all the upper primary school Zilla Parishads in the rural areas. The work of placing compressor, tractor and pumping sets and providing facilities to the farmers for deep fog was also entrusted to the Zilla Parishads.

When the drafting of the third Five Year Plan (1961-66) of the state was taken up in the year 1960, it was thought that the scheme should be constructed in accordance with the spirit of democratic decentralization. Firstly, the gram panchayats formulate their Panchayat sector five Year plan in consultation with the Gram Sabha based on their basic needs, development potential and their own financial and natural resources. The Panchayat Committee will cooperate with them. Based on the scheme of Gram panchayats, a five-state plan for the Panchayat committee area will be prepared. Covering all these, the District Council will formulate a five year plan. The state five year plan will be constructed by incorporating the schemes of all the districts.

The development rights and all PRASAR officers have been involved in the meetings of Gram panchayats for nearly a month to coordinate the construction of the five year plans of panchayat areas and to provide guidance as per the needs. For the first time, gram panchayats were entrusted with such an important responsibility. The Sarpanch and all the members of the Gram panchayats were thrilled and very enthusiastic that the government, for the first time, considered it worthy of planning the development of their region. The gram panchayats were initially made clear that they should not prepare any charter of demand but plan for development based on their strength and resources. They were also pointed out as to how much money they would get from the government in the form of grants in the next five years and what are the schemes for which they could receive from the government. They were also reminded how much contribution they could get. They were also reminded of the powers of their taxation under the Panchayat Act and how much revenue they can earn from their use. It was an exciting experience for all the gram panchayats to participate in these meetings. The methods of the development of the area from the illiterate villagers ' own experience and common sense to the system of providing resources were actually basic and practical. When the gram panchayats presented these five year plans in the Gram Sabhas, the entire rural zone of the state was infused with a strong sense of enthusiasm, self-confidence and self-reliance.

The Panchayat committee meetings discussed the schemes of gram panchayats. The collector and all other district level officers were present in the meetings. All technical and practical suggestions were made by all, based on which the draft Panchayat Committee's five Year plan was unanimously finalised.

In the district councils meetings, the proposals submitted by the Panchayat committees were discussed in depth. All their thoughts and suggestions about the spirit of all round development of the district are raised above the political blockade. In these meetings, apart from the pradhans and development officers, the District collector, all the districts level officers and regional Development officers (Zonal developers officer) from divisional headquarters participated.

The innovative spirit of decentralised decentralization and swavalamban, which was created at the local level, from the village panchayats to the district level, was an unprecedented phenomenon of our development journey. But it is really unfortunate that this democratic process of planning, not the Trinamool, has been pursued. The entire planning process remained confined to the chambers and corridors of the Government of Jaipur and the Planning commission of Delhi.

Indo-Pak War of 1965

In the year 1965 when Pakistan invaded India, many villages on the international border of Rajasthan faced the menace of war. In the hour of that national crisis, our gram panchayats performed the role of security watchdog. He guarded his region by monitoring the railway lines, electricity and telephone and telegraph pillars, roads, bridges and drinking water sources day and night. He also took care of the dependent families of the soldiers residing in their areas. He awakened and organised public consciousness in that hour of national crisis and strengthened the morale of the people.

Thus, development and security, war and peace are the important contributions of Panchayati Raj institutions in every situation. Shri Sukhaadia will always be remembered for strengthening the Panchayati Raj institutions and handing them meaningful participation in power. His reign was undeniably the golden era in the history of Panchayati Raj institutions.